Journal 10 March 2019

Core disciplines at the Suzhou China Centre

We explore four of the disciplines at the heart of the China Centre’s illuminating new programme

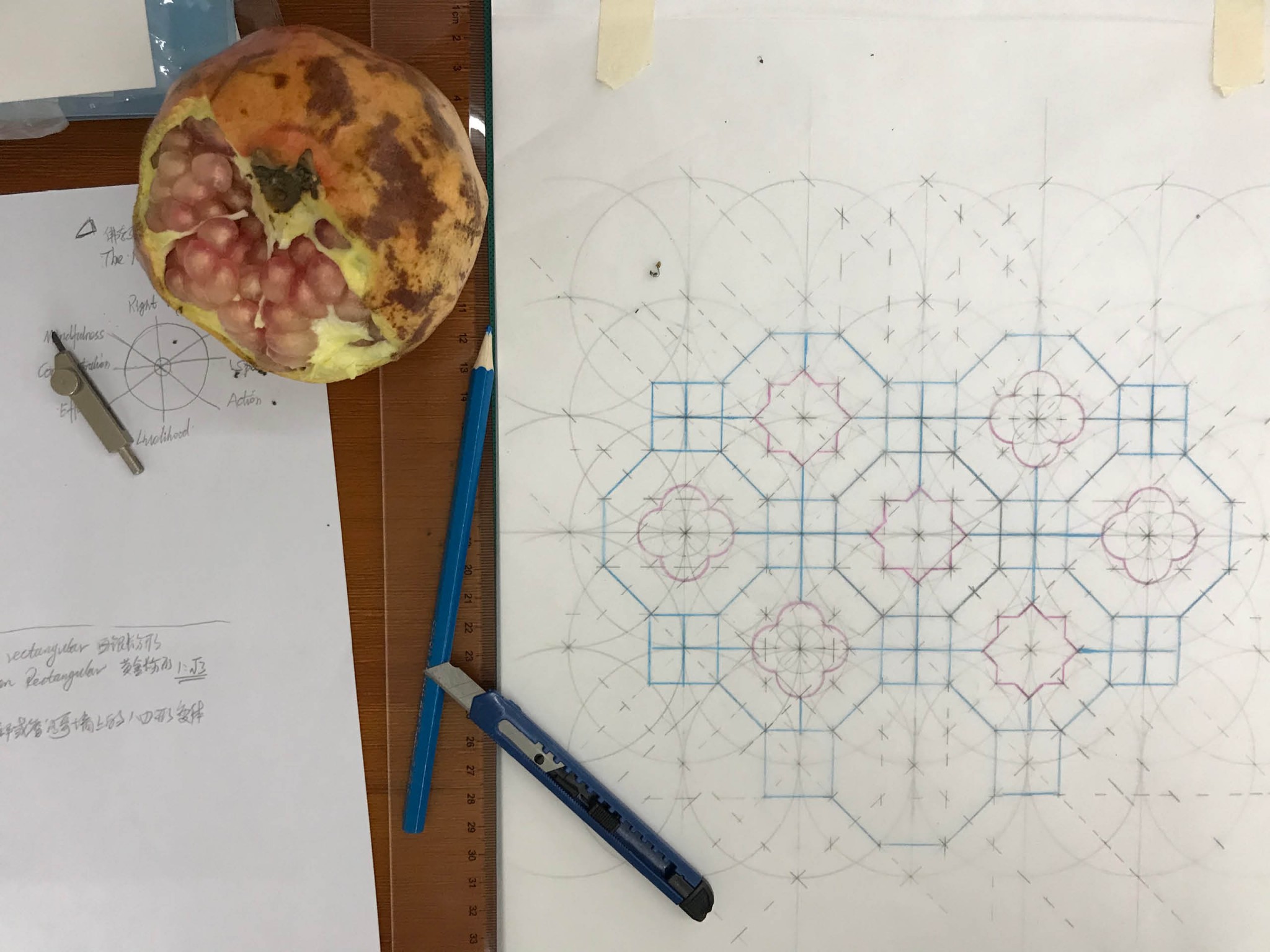

Garden design

“One of the most fundamental concepts of Chinese garden design is the notion of ‘less is more’,” says Ye Fang, whose Nan Shi Pi Ji garden in Suzhou is the only contemporary Chinese garden design on UNESCO’s list of the city’s classic gardens. Established among the greats of the discipline, Ye Fang describes his craft as a cross-disciplinary art form that integrates many of the aesthetic principles found in Chinese painting and poetry, as well as architecture, interior design, opera and even culinary arts.

“When one understands the essential nature of things, then the grand design of nature itself can be represented with elegant simplicity,” he says. “In the structure of the Chinese garden, mountains and water are protagonists; flowers and plants have supporting roles; while pavilions and platforms have a more decorative function.”

Ye Fang’s course at the Yuan Centre will see students immerse themselves in the classic elements of Chinese gardens. As well as learning to identify the key elements, they will learn how to transform theory into reality, while also examining the artistic aspects of the garden designs through landscape paintings and poetry.

Silk weaving

Throughout its 2,500-year history, the development of Suzhou has largely depended on the canal system and the silk trade, visible through the waterways and workshops spanning the city. “Archaeological evidence of silk weaving dates back to the Palaeolithic period,” says Guohe Wang, a professor at Suzhou University. “In the Ming and Qing periods, the majority of the silk-producing workshops in China were located in the Suzhou area. Silk became both an important trade product and a symbol of China’s artistic achievement.”

All of which makes it a perfect place to study the art of silk weaving. At the China Centre, Wang’s course leads students through a study of silk culture, fabric structure and aesthetics, as well as the role of textiles in daily life. “Clothing is a basic need, not only for its function, but also for its aesthetic and symbolic value,” he says. “Working with the physical objects, including different types of textile examples and weaving tools, will help students develop an intuitive understanding of both the aesthetics and production process.”

Feng Shui & Geomancy

According to the China Centre tutor Ding Xiyun, feng shui, which translates as ‘wind-water’, is a theoretical framework that examines the relationship between humans and nature. “Humans are part of nature and should act according to its principles,” he says. “In a concrete sense, feng shui is about making decisions with regard to what kind of geographical features are suitable for living.”

At its heart is the theory of qi, or energy flow, which generates the elements of feng shui – qi in its moving form generates wind, and in its concentrated form becomes water. Understanding the relationship between qi and feng shui is of fundamental importance, according to Ding Xiyun. Examining elements such as water sources, sunlight, wind and land fertility, this course, which is taught alongside geomancy – the practical application of feng shui – gives students a grounding in identifying these principles across a wide range of art forms. “Landscape paintings and gardens are reflections of the Chinese understanding of the relationship between humans and nature,” says Xiyun. “Feng shui and geomancy are thus traditions closely tied to the Chinese experience, and offer very different perspectives vis-à-vis Western traditions.”

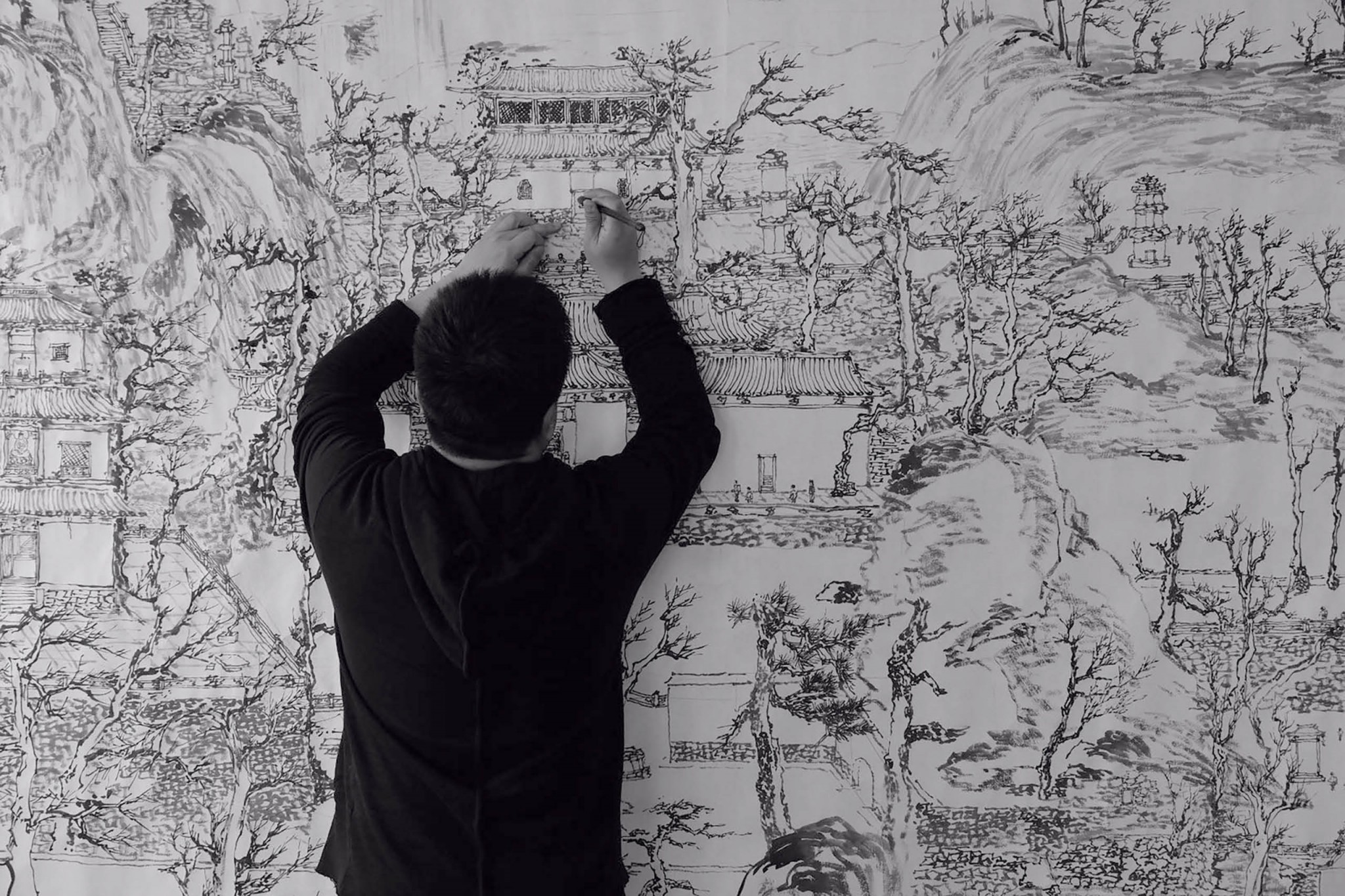

Landscape painting

“The tradition of Chinese shan shui painting, which translates as ‘mountain-water’, is a distillation of past masters’ experience of travelling in the mountains,” says Lin Haizhong, a professor in the traditional Chinese painting department at the China Academy of Art in Hangzhou. “Shan shui represents the highest achievement of Chinese art, and the depth of scholarly research on the aesthetics of Chinese landscape painting is unparalleled.”

A big believer in the practice of painting as a spiritual pursuit, Haizhong’s course at the China Centre explores shan shui paintings, the connoisseurship of which is a key element of learning for new students. “The focus will be on the principles of painting rockery and flora – the two basic elements in Chinese shan shui art,” he says. “Students will learn brushwork and ink techniques, structural composition of the landscape, and the technique of painting shades and textures, known as ‘cunfa’. Part of the course will also be dedicated to the topic of shan shui aesthetics.”