Journal 18 July 2018

Keeping traditional Islamic architecture alive in Saudi Arabia’s historic town of Jeddah

A pioneering partnership between the Prince’s Foundation School of Traditional Arts and Jameel House is helping ensure its heritage endures for future generations

Across the street from the Jameel House of Traditional Arts in Jeddah sits the imposing Jamjoom House – one of the most striking buildings in Al-Balad, the city’s historic old town. Its warren of rooms – which once housed the living quarters of the Jamjoom family, stores for merchants’ wares and a great comptoir, where goods were weighed and deals struck – now lies dormant, its vital role at the heart of civic life confined to the past.

A similar story can be found across Al-Balad, illustrating huge social and economic shifts in Saudi Arabia’s second city. Now home to four million people, it was Jeddah’s commanding position on the Red Sea that saw the city evolve as a major port in the seventh century. As a gateway to the holy city of Mecca, it has welcomed pilgrims and traders from around the world ever since, with its key position at the centre of the Islamic world shaping its rapid growth and leaving a lasting legacy on the old town.

“Jeddah’s heritage has been enriched by influences from all corners of the Muslim world – Africa, South Asia, the Levant and beyond,” says George Richards, Head of Heritage at Art Jameel. “Jeddawi dialect has loan-words of distant origin and its cuisine is rich with dishes from Java and Bukhara.” Jeddah’s complex history is also reflected in the architecture of Al-Balad. Here, tower houses are made of coral stone from the Red Sea and teak from the Indian Ocean, and facades are adorned with intricate lattice window frames and carved gypsum panels that bear motifs of South Asian, East African and Levantine origin. But following the 1970s oil boom, many old families left the old town as modern suburbs sprung up beyond its perimeter, with architects’ concrete-and-glass vision of modernity becoming the norm. Meanwhile, Al-Balad’s more transient newcomers neglected to maintain the traditional buildings that were once so majestic.

“The crisis that Jeddah has been facing is common to a lot of medinas in the Arab world,” says Khaled Azzam, Director of The Prince’s Foundation School of Traditional Arts in London. “These lively urban environments were allowed to grow organically for hundreds of years before a more modern approach to urban planning came in, which led to the death of traditional arts and crafts.” Although Al-Balad gained UNESCO world heritage status in 2014, Azzam feels that this has come too late to save many of the buildings. “It’s a unique city that has been undervalued – it’s been falling apart for the past 25 years,” he says. “Things are more controlled now but it has come too late – there’s a huge amount of water damage throughout the city and many buildings have collapsed or caught fire.”

Hope for Al-Balad’s future lies in its youth – hence a partnership between Art Jameel and The Prince’s Foundation School of Traditional Arts, which offers students the chance to understand the cultural and artistic heritage of the old town through its symbolism and craft techniques. The Jameel House of Traditional Arts in Jeddah offers a one-year course designed to teach students techniques – including the language of geometry, arabesque forms and materials – that reference the past but that can be interpreted for contemporary use. Although many of the buildings in Al-Balad are beyond repair, Azzam hopes the programme can help keep Jeddah’s history alive. “We say that this is a ‘living tradition’ and all we can do is teach these techniques to the younger generation. The best thing you can do here is to enable young people to take ownership of their cultural heritage.”

The setting couldn’t be more inspirational. Students are immersed in the heart of Al-Balad, something that they find essential to their discovery of the traditional arts, according to Richards. “Students visit historical houses on their field studies, climbing ladders and taking rubbings of gypsum panels, or examining fragments of ancient mangour [an ancient Hijazi craft] among the debris of a collapsed house,” he says. “The daily walk through the streets of the old town fills the students with a deeper understanding of their work and of the importance of their role as a link between the heritage of Jeddah and its artistic future.”

Glimpses of this were showcased among students’ final projects this year, which included a mihrab (prayer niche) and roshan (traditional wooden window frame). According to Richards, this demonstrates their potential to restore and preserve Al-Balad’s heritage. “At Jameel House in Jeddah, we are nurturing a new generation of artisans and artists with craft skills and the understanding of traditional arts necessary to support authentic restoration of the built heritage in the old town.”

Recent graduate Joud Hourani recognises the significance of her studies at the Jameel House of Traditional Arts. “Cultural and arts preservation is essential as it’s a treasure to pass on to the future,” she says. “I’ve always had an interest in cultural preservation through art, and this course covered a large aspect of traditional arts in Jeddah.” Having completed the year-long course, Hourani hopes to help spread knowledge and awareness of Jeddah’s “precious and mystic” Al-Balad.

Azzam has seen a change in attitudes towards Jeddah’s heritage in recent years, which bodes well for the future. “I don’t know how much of it is down to us but there is more awareness and we see a lot more restoration thanks to a government programme to restore the old mosques.” He’s witnessed creatives move into the area and says Al-Balad now boasts a new wave of coffee shops and innovative food venues as a newfound dynamism starts to pick up.

Last year, Art Jameel worked with digital technology experts to train a team of Saudis in photogrammetry and a range of high-resolution recording techniques. Together they scanned and recorded some of the key sites in the old town and the resulting open-source data will support researchers and conservation teams, as well as budding artisans enthusiastic to keep the spirit of iconic sites such as Jamjoom House alive. “Today, Jeddah’s artistic community is vibrant and exciting,” says Richards. “It reflects its past but is also thrillingly contemporary, weaving a link between the city’s heritage and the new ideas engaging artists around the world.”

Craft mastery

Exploring four enduring elements of Islamic design

Geometry

The abstract use of geometric forms based on repetition of circles or squares can be found across Islamic architecture and as a common decorative element. “Geometry is very important as it’s not just about pattern but about how visual language and structural elements come together,” says Khaled Azzam of The Prince’s Foundation School of Traditional Arts.

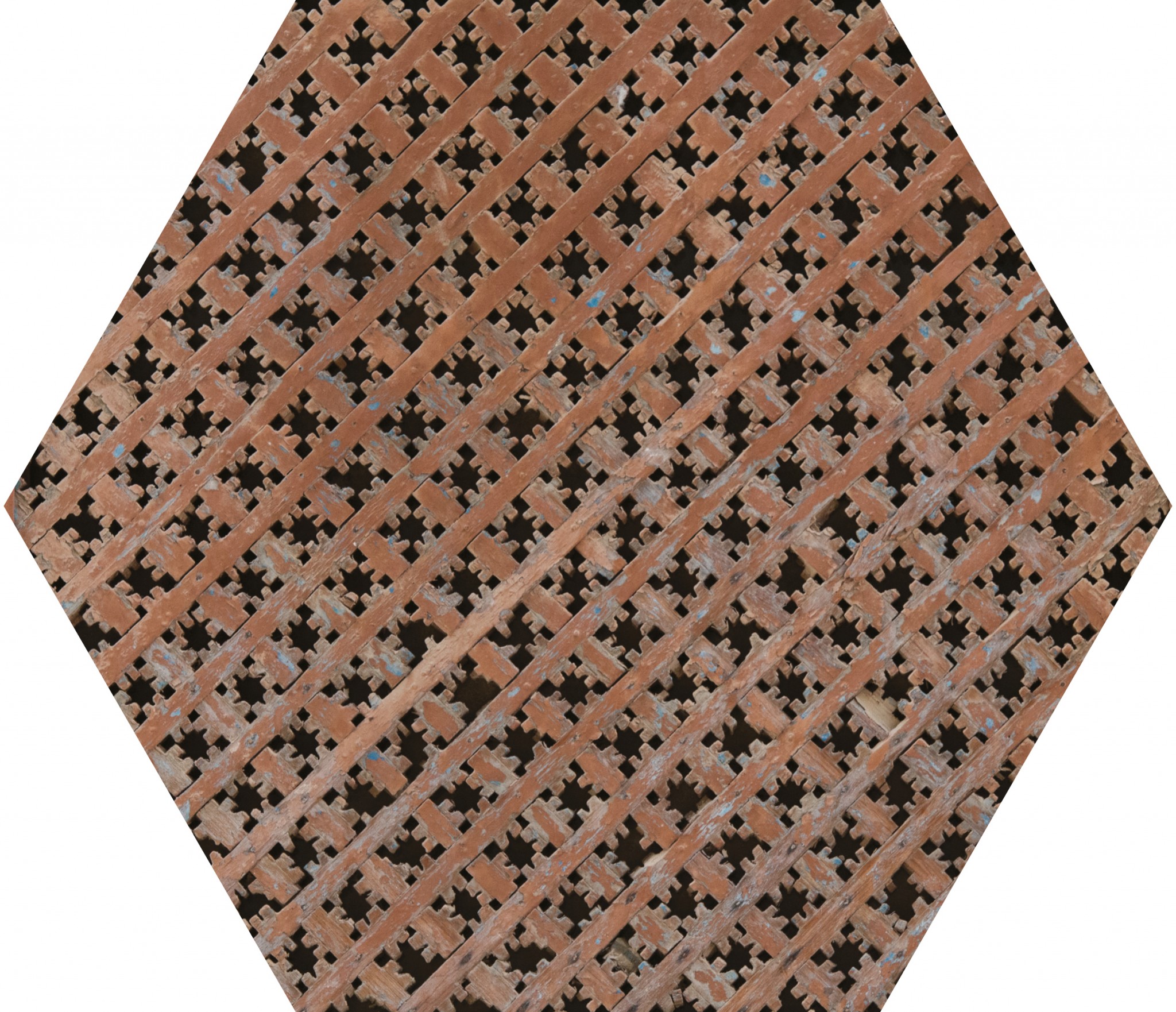

Mangour and parquetry

As seen across the roshan balconies in Al-Balad, mangour is a form of woodworking featuring elaborate latticework. “As Jeddah is very humid these wooden screens on balconies were perforated allowing air to move through,” says Azzam. “But they are also very beautiful decorative elements that define the architecture.”

Nabati ornaments

“This is what we call biomorphic form and what the west calls ‘arabesque’,” says Azzam. “Nabati means of the flower or vegetable, and is an interpretation of the natural world.” At Jameel House, students study the formal Ottoman tradition of islimi (lines, design and colour techniques) and move onto the exploration of patterns and designs found in Jeddah’s old town.

Gypsum carving

“The decorative arts of Al-Balad are mainly executed in gypsum, seen in the geometric and floral patterns that adorn facades, gateways and parapets,” says Azzam. “This skill has been fading, so we teach young people to understand the technical aspects but also, through application, to understand how craft technique is used to express an artistic language.”