Journal 5 February 2019

The Prince’s Foundation partnership with MYB Textiles

Tech and tradition combine to revive the fortunes of the Ayrshire lacemaker

Standing on the factory floor at MYB Textiles is a fascinating, if not deafening experience. The 100-year-old lacemaker’s 20 Nottingham lace looms and six Vamatex madras looms punch out a loud, hypnotic beat.

Ayrshire’s weaving origins are less harmonious: Protestant Flemish refugees fleeing Catholic persecution in Europe brought hand looms to the Irvine Valley towns in the 16th century. The rivers kept the threads needed for the textiles slightly damp and therefore malleable. It was this steady climate that enticed lacemaking companies including Morton Young and Borland (now MYB Textiles) to the area in the late 1800s. “When owner Alexander Morton introduced new mechanised looms in 1913, the damp was also perfect for keeping their pattern cards in perfect condition,” explains Margo Graham, MYB’s operations director. “If the cards get too dry or too wet the patterns distort and the lace is ruined,” she says.

Time has not been kind to the mills in this area. The combined force of cheap global manufacturing and a lack of training for succession has brought on the closure of almost all the local textile factories; MYB is now the last lace and Scottish madras producer in the area. So how are they succeeding where so many have failed?

“We’re constantly adapting,” explains Graham. “The company weaves baby blankets, theatre cloths and creates textiles for films with an ever-growing international client base.” Highlights include set dressing for the Wes Anderson film, The Grand Budapest Hotel, and supplying The Ned hotel in London with art deco-inspired curtains created from their huge archive.

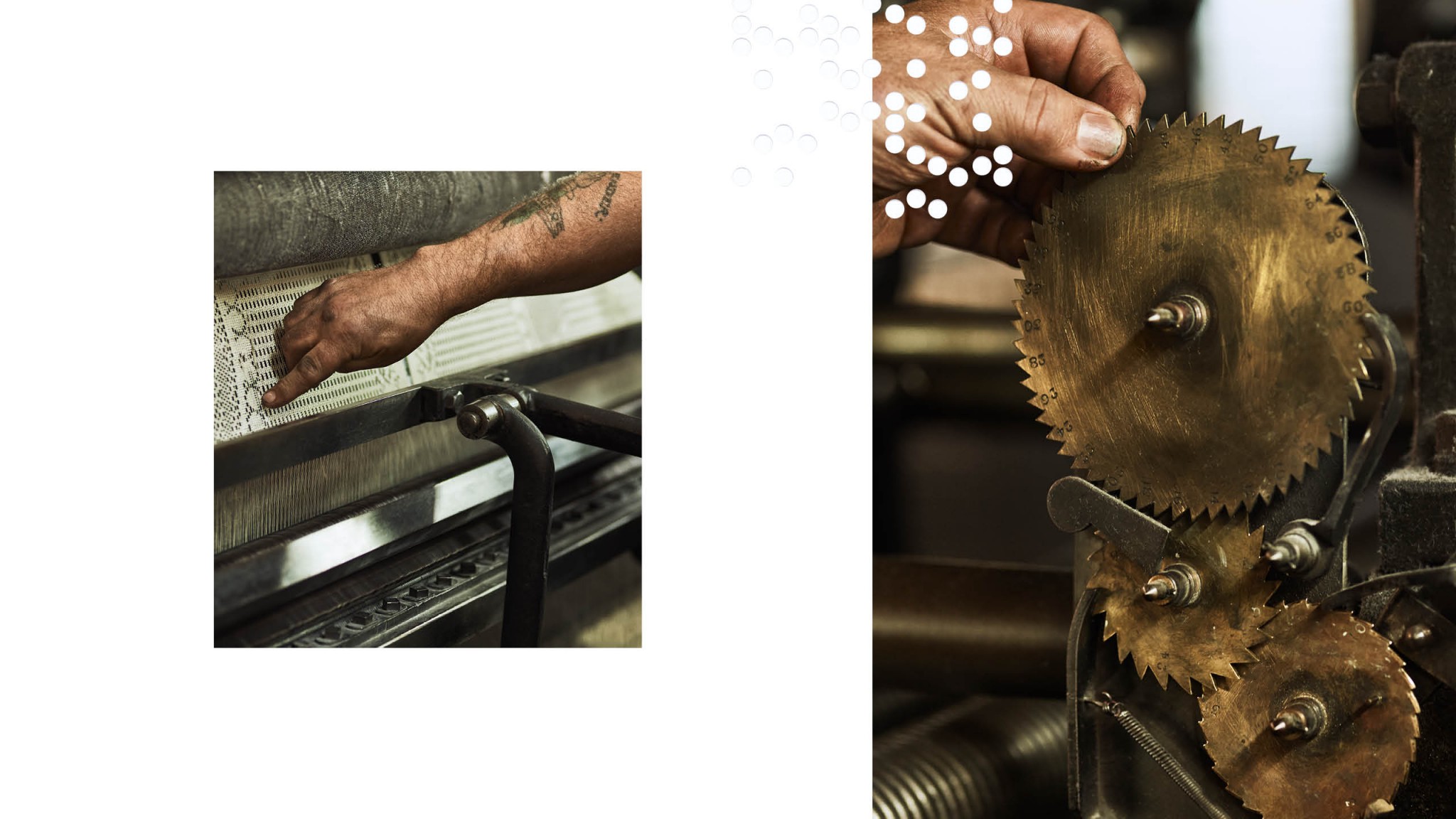

The equipment is adapting too. A loom follows instructions held in perforated cards threaded together and suspended above the machine. Each hole position in the card corresponds to a hook, which can either be raised or lowered depending on whether the hole is punched. The hook raises or lowers a harness that carries and guides the thread. This sequence of raised and lowered threads creates the pattern. Originally these patterns were created by a draftsman and a puncher would punch out the pattern by hand: a timely and therefore costly process. However, 25 years ago the company converted to computer floppy disks that instructed a hole-punching machine.

Technology moves fast; floppy disks are now obsolete and while local tech and engineering students are working on solutions to transfer this information, a local inventor Michael Litton has already revolutionised the weaving process. Litton converted Vamatex harnesses to work via CAD-controlled computers networked by fibre optic cables and attached them to the century-old looms. This replaces the punch cards and allows for incredibly complex patterns to be woven in a much shorter space of time.

However tech alone does not sustain production. Engineers are trained over decades. “Their skills are normally handed down from father to son,” says Graham. “They’re so attuned to the machinery that they can tell if a draft from an open door will affect their loom’s performance.” Once off the looms it’s the careful eyes and exquisite hand-sewing of the darners that MYB rely on to take their product to the next stage. They look for faults in the weave before reconnecting the broken patterns with delicate stitches. Training is long. “When you first start here, you’re taught to draw all the patterns by hand,” says employee June Campbell. “Once you’ve mastered that you practise the patterns on a piece of rag for a minimum of six months.”

This is where The Prince’s Foundation’s partnership with the mill is key. “We want to help ensure companies like MYB have the workforce to survive and grow,” explains Jacqueline Farrell, Education Director for Dumfries House. “We have been fortunate to have fabric donations, guest talks at industry insight events, and mill tours.” On these tours all aspects of lace production from design and weaving to finishing and packing are on show.

Will exposure to this heritage industry pique the interest of the perfect trainees for the mill? Farrell is confident it will. “We know that someone with great attention to detail and an ability for excellent hand-sewing will fit MYB’s needs so it’s a case of us talent-spotting our trainees.”

The Foundation’s educator has big plans for this industry collaboration. “We would like to help develop more finished products with them using lace so that they can reach new markets and our trainees would get experience of sewing challenging fabrics to a high-quality standard,” says Farrell. With such vision it seems unlikely that this unique textile will be relegated to history.