Journal 10 February 2019

An interview with Nansledan architect Hugh Petter

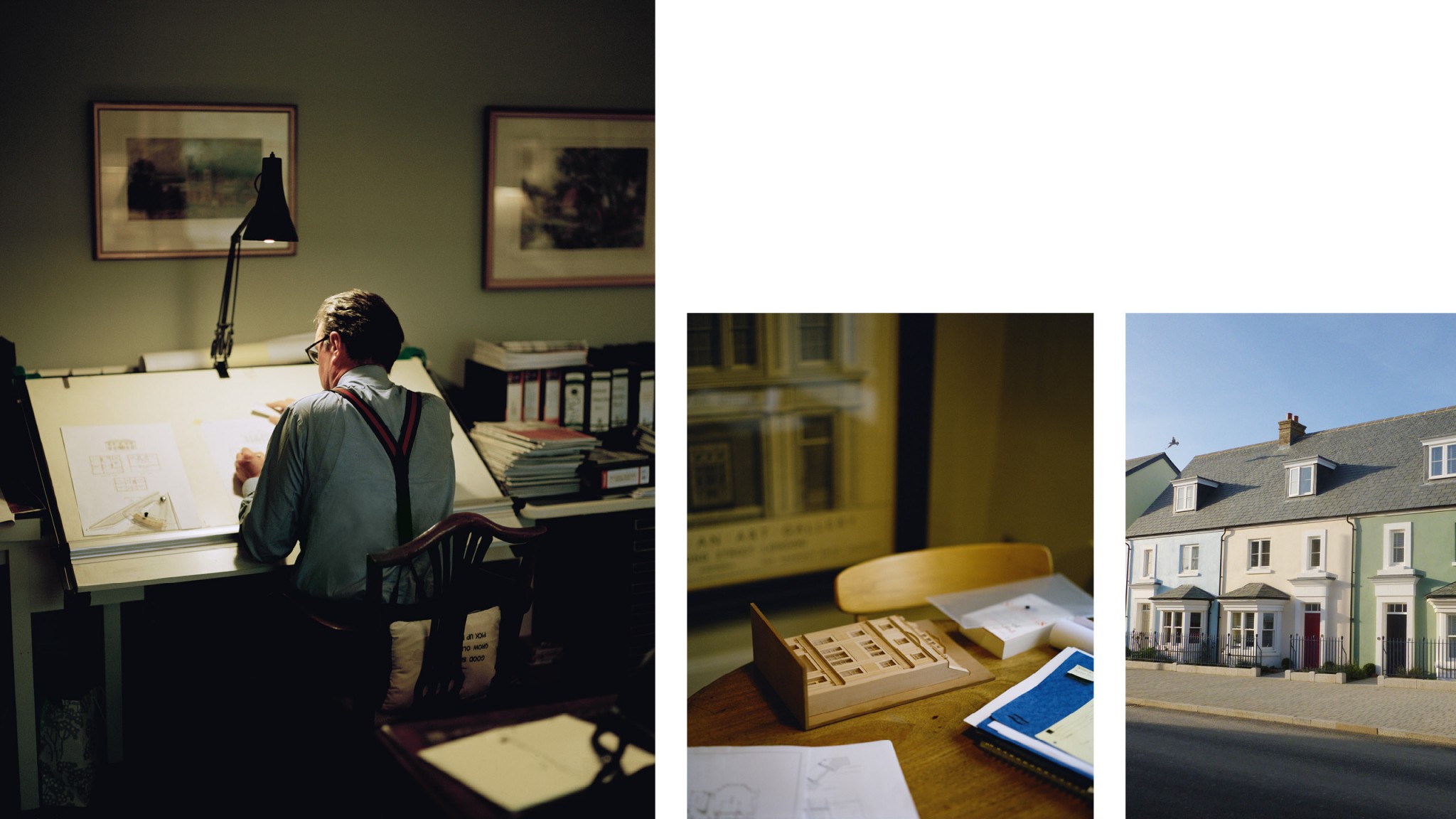

A new housing project in Cornwall is changing the way we approach sustainable developments, as master planner and lead architect Hugh Petter reveals

On the north coast of Cornwall, the popular seaside town of Newquay is in the midst of a rebirth that will change its geography forever. Just a short walk inland, a town extension of 4,000 new houses, a high street, church and school at Nansledan will, over a 40-year period, galvanise Newquay, which has suffered in recent years from a lack of affordable housing and jobs, and a transient workforce. With local suppliers and materials used throughout the development, the jobs created in the construction and implementation of Nansledan will enable people to live, work and educate their children in the area, and it is hoped that a sense of community and identity will flourish.

Unlike any other housing development of its scale and vision, Nansledan has been led by the Duchy of Cornwall, which owns most of the land the development will be built on, and The Prince’s Foundation, which uses the project as a case study. Defined by forward-thinking approaches to ecology, environment and the existing townscape, it’s hoped that Nansledan – which means ‘broad valley’ in Cornish – will prove a development that will influence future schemes.

Hugh Petter is the director at ADAM Architecture and worked closely with HRH The Prince of Wales and the Duchy on the project. The former Prince’s Foundation trustee has won four awards for Tregunnel Hill – an urban infill scheme in Newquay seen as a precursor to Nansledan – which has already been completed. Now, as the first brightly coloured houses at Nansledan are finished, we asked Petter what makes the development unique, and what to expect as plans become reality.

How did the local authorities impact the development?

Amazingly when the project kicked off, Cornwall Council told The Prince’s Foundation to forget the normal five-year planning window and instead take a 50-year view on what Nansledan and Newquay could become. This allowed the project to evolve into a significant extension of the town. The council were visionary in recognising the benefit of long-term strategic planning, which means you can start to plan things like schools and develop them incrementally.

What was the process behind determining Nansledan’s aesthetic?

I was commissioned to produce an architectural and urban pattern book for Newquay. Pattern books – shared examples of architectural design – exist in America, but aren’t used as much in the UK. We plotted the characteristics, including the different styles of street, along with their scale and character, and the typologies and architectural details of each building, as well as information about the plant life that exists in a marine environment. This became a bible for designers to make sure that any new structures or community spaces resonated with the town’s existing character.

How effective did the pattern book prove?

It was extremely effective in getting the people of Newquay to look at their town in a different way and not think of it as a run-down place. A lot of the local residents said they had never looked above the line of empty shops to see that there were some quite grand buildings, and this helped them to feel excited about what their town could become again. Off the back of that, we held a public consultation to establish what the needs of the local people were.

How will the Nansledan development affect Newquay as a whole?

In Newquay there’s an historic centre and lots of 19th and 20th century suburban development, which is very monocultural and reliant on people driving to one place for the shops. Introducing mixed-use quarters means the town will benefit economically and socially from people visiting Nansledan in addition to the centre of Newquay to do their shopping, helping to create a more sustainable and less centralised pattern of living for the whole town, not just the new residents.

What impact will Nansledan have on the local environment?

The ambition is to enrich the ecology of the area, which was previously poor-quality agriculture. One approach we took was to look at food: we’ve promoted edible urban planting, so a lot of the front gardens have herbs and berries, and most of the trees are fruit or nut trees. There are also allotments, which are located close to play areas so that families can take their children to the swings and tend to their vegetable patches at the same time. We also have bricks made with china clay waste, which house bees to help with pollination. We also worked with the RSPB and have swift boxes on many houses to encourage nesting.

Were any lessons taken from the Duchy’s Poundbury development?

The lesson from Poundbury, an urban extension on the outskirts of Dorchester, Dorset, was that doing something on a larger scale can be an opportunity to regenerate existing towns while providing sustainable new areas for development. But in terms of the design, they are very different. Poundbury was relatively high style as Dorset is, and was historically, a richer part of the country. With Nansledan, being on the Atlantic means buildings become more weather-worn, so the opportunity for detail is less than with houses located inland. But where there are details, they are beautifully considered – for example, we used Cornish granite and slate on windowsills and roofs. A lot of the aesthetic impact is through the use of strong colour, which takes from the seaside tradition. That has proven very popular.

“The chance to create better places for people to live is something I’ve found inspirational”

How did you decide on place names?

In Cornwall you normally have the names in English as well as Cornish, which makes for enormous signage. Our approach was to declutter, so we agreed with the council to only use Cornish names on signs, created in a distinctive slate. In terms of the names, HRH The Prince of Wales was very keen on coherence; the legend of King Arthur was taken as one source for the street names in one direction, and a list of local fields and settlements in the other direction, giving rationale to the warp and weft of the town’s fabric.

What was your experience of working with the Duchy like?

My career has developed in line with a lot of HRH The Prince of Wales’ interests, and working on a project of this scale and longevity has been a privilege. The chance to explore and develop ideas to create better places for people to live is something that I’ve found inspirational. Having spent a long time developing Nansledan, we’re just starting to see what comes out the other end. There’s a whole movement taking off right now with a groundswell of opinion across the country about how we can deliver better architecture, which in turn helps landowners provide what people actually need.

What defines a successful housing development?

Housing that’s beautiful, enduring, recognisably of a place and fits with people’s lifestyles. Quality of life is now at the forefront of people’s minds when looking for a home, and I worry that big developers are not responding to that need, and are instead producing more monocultural housing estates that don’t reflect this shift in mood of the younger generation.

A Pattern of Success

The project’s pattern book outlines defining characteristics of buildings in Newquay and has served as the blueprint for the overall aesthetic of Nansledan. Here are a few of the highlights

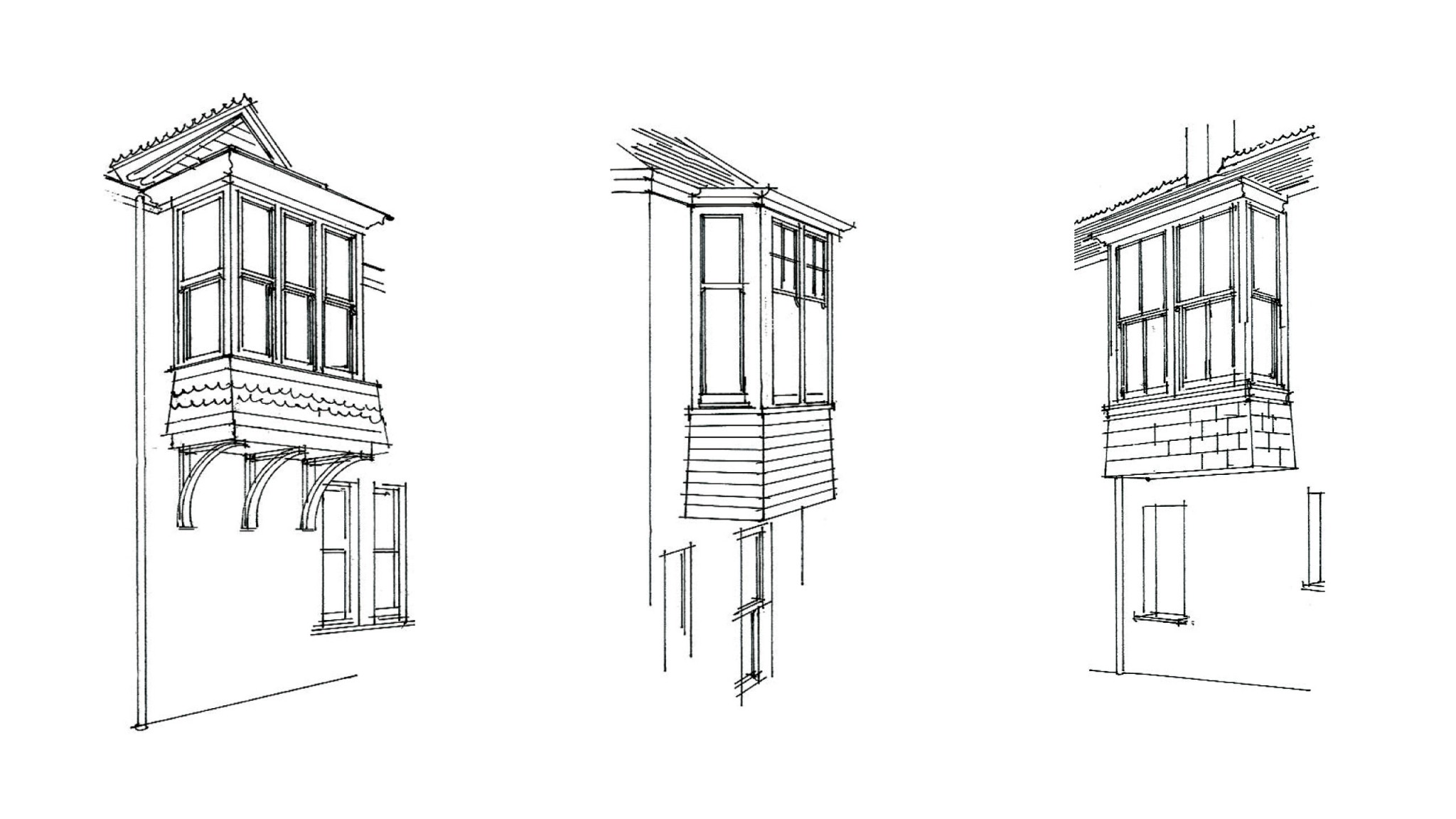

Oriel windows

A key building feature in Newquay, oriel windows give good views from upper floors and save space at ground level by projecting out

Gables and bargeboards

Decorative and profiled bargeboards commonly feature in Newquay and contribute to the ‘Riviera’ character of the town’s buildings

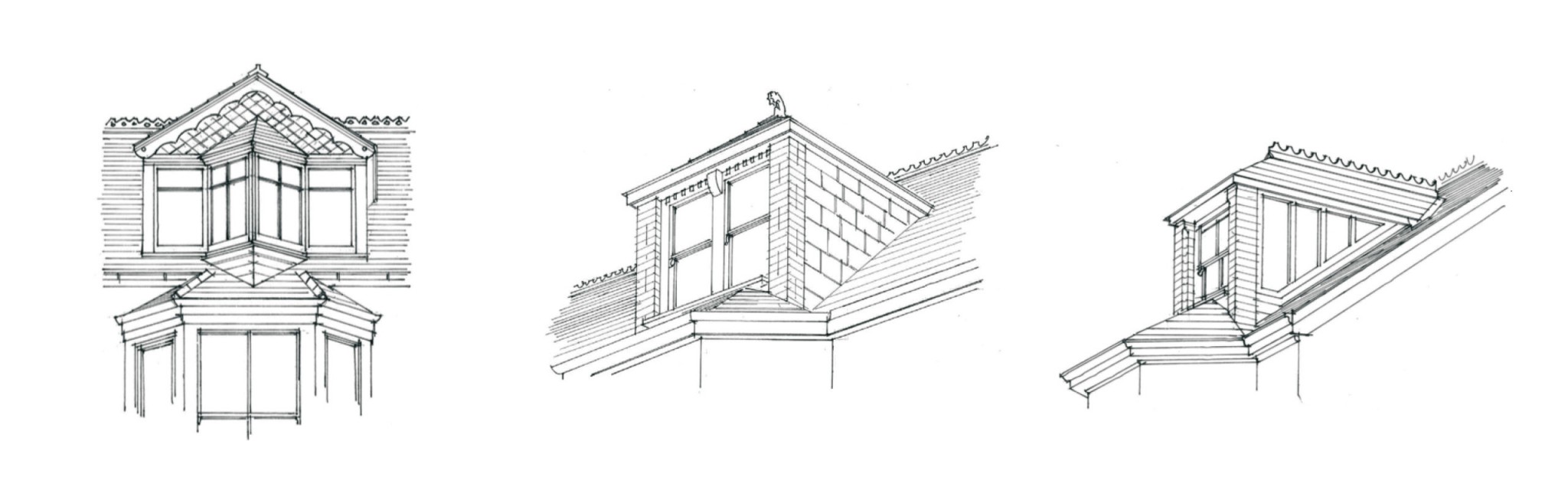

Roof Dormers

A variety of dormer styles can be found on the buildings in Newquay, including glazed dormers and square dormers with decorative roof finials

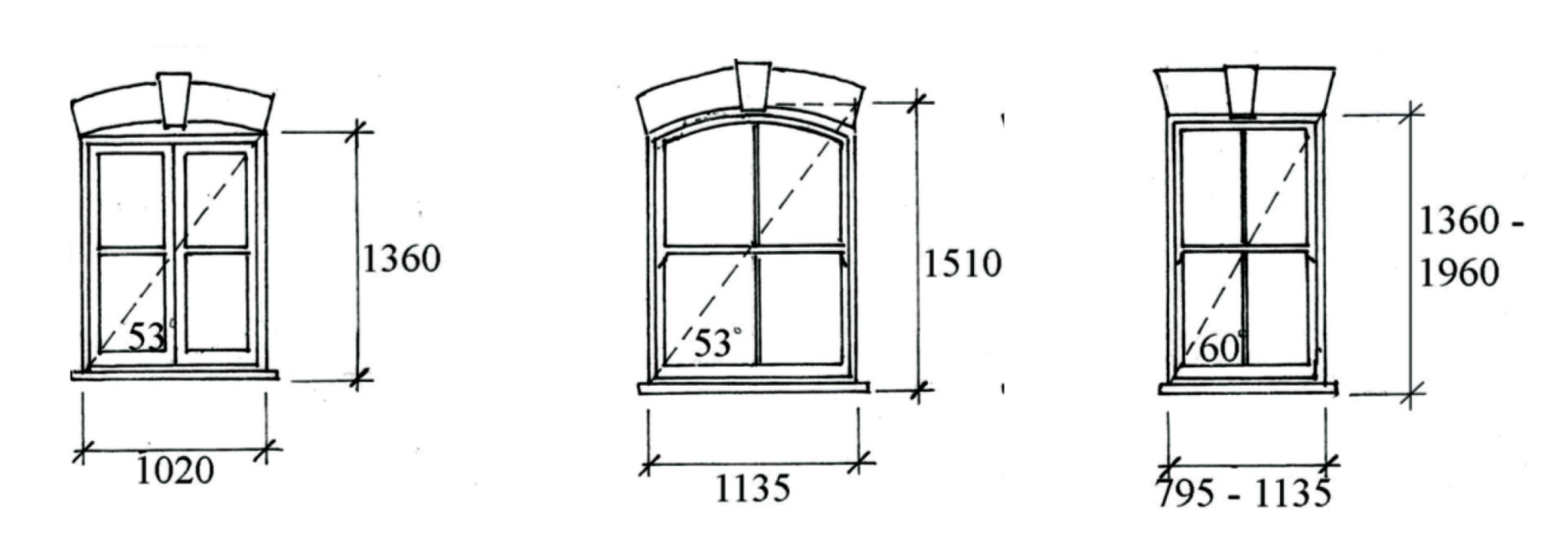

Cottage Windows

Many of the windows on the town’s cottages are sash or side hung casements with a simple arrangement of glazing bars and softwood frames