Journal 18 February 2019

Preserving the British textile industry

The reshoring of the UK textile industry is in motion, but what does the future hold?

Do you know where your jacket comes from? Take a look inside and check the label. For most people, the likelihood is that ‘Made in Bangladesh’ or ‘Made in China’ will be written there. It’s hard to imagine a time when the UK was a major force in the garment and textile industry, supplying products for both luxury and high street brands, and in turn sustaining communities across the country and tapping into local skills.

However in the late 80s, the industry took production overseas, where competition for cheap labour all but decimated this part of the fashion sector. Factories closed in towns such as Hawick, Blackburn and Huddersfield, nearly eradicating knitwear, cotton woollen and worsted production, and effectively ending entire districts’ ability to make money.

But British manufacturing is making a comeback. In part bolstered by favourable exchange rates (the price gulf between China and the UK is narrowing) the cost of logistics, transport and minimum orders versus quality on deliverables is now no longer as attractive.

Provenance – the knowledge of where something has come from – is also increasingly informing purchasing options. Emerging economies around the world are buying into heritage brands, while we are all now starting to care about where our products are made and the environment in which that occurs. The reshoring of textile and garment manufacturing can only be a good thing for our economy, but these new opportunities also present challenges, so how can we ensure this revival is an enduring trend, not merely a passing fad?

John Sugden, former Mackintosh Sales and Marketing Director and Director of highland tailors Campbell’s of Beauly, alongside Patrick Grant, owner of Savile Row tailor Norton & Sons and ready-to-wear label E Tautz & Sons in 2009 (for which he won the Menswear Designer Award at the British Fashion Awards in 2010) are co-chairmen of the Future Textiles programme, an initiative set up in 2014 by HRH The Prince of Wales with the goal of training the next generation of skilled textile and garment employees in the UK. We caught up with them and Dumfries House Education Director Jacqueline Farrell to talk about how to face the future of fashion manufacturing head-on…

What role do you play in the initiative?

Patrick Grant: We’re part of a growing sector within the fashion industry that recognises the need to get more young people interested in this craft, and to find routes to good employment for people being left out by the current educational system. John Sugden: Both Patrick and I have our own manufacturing companies, so we are at the coal face each and every day, dealing with problems that very often relate to a shortage of skills. We are therefore well placed to advise how we can rectify this.

What’s Future Textiles’ goal?

Jacqueline Farrell: To teach young people the difference between fast fashion and heritage manufacturing. What does that entail? We look at quality – why garments should be made to an exacting standard – and why they should be priced fairly in relation to the process of how they are created, which encompasses both worker and animal welfare. Our workshops in The Atelier at Dumfries House teach 12 to 18-year-old students in schools Scotland-wide, as our initial research indicated that this demographic in particular don’t possess the skills or have an interest in sewing.

What are you doing specifically to get people into work now?

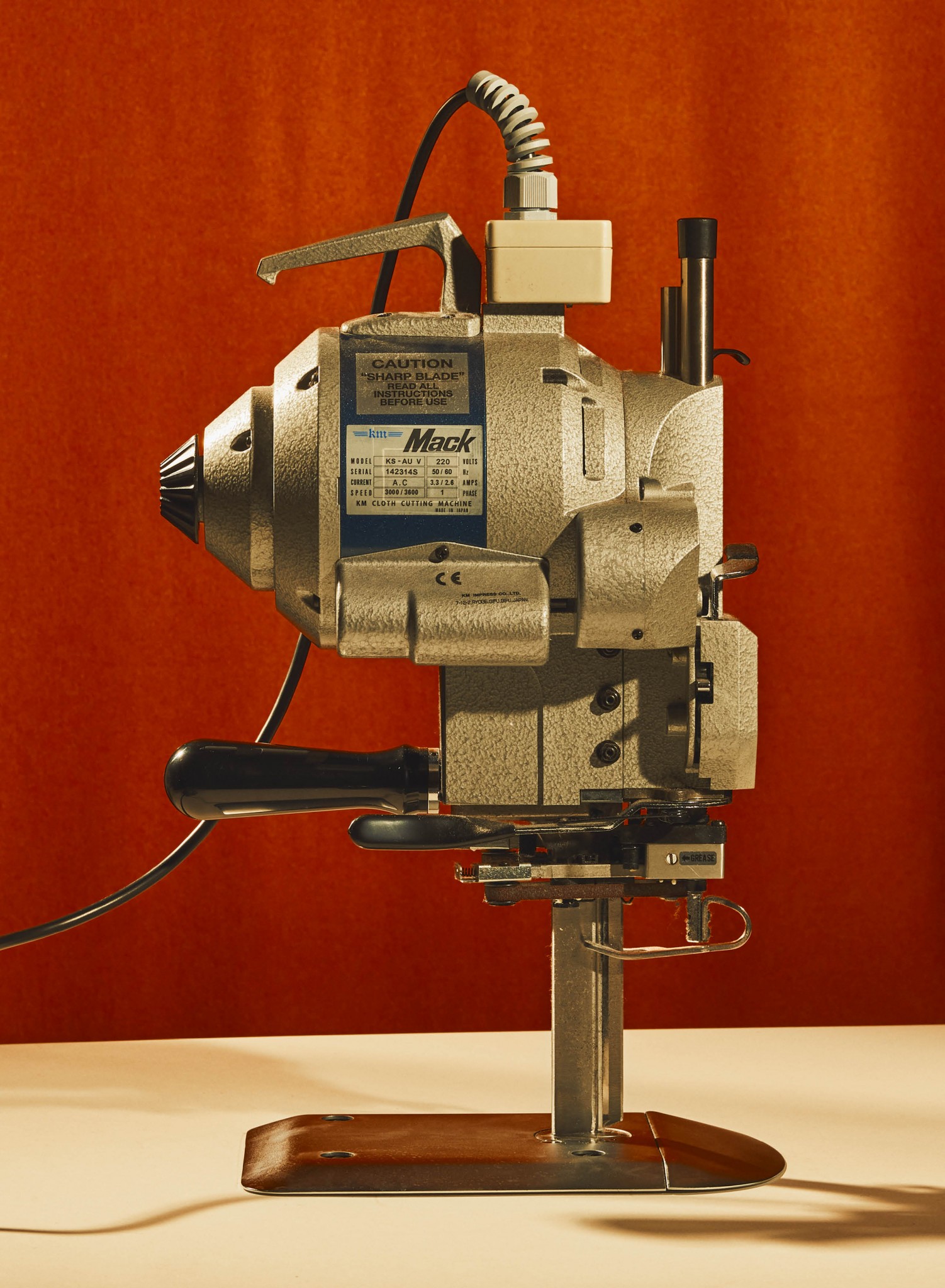

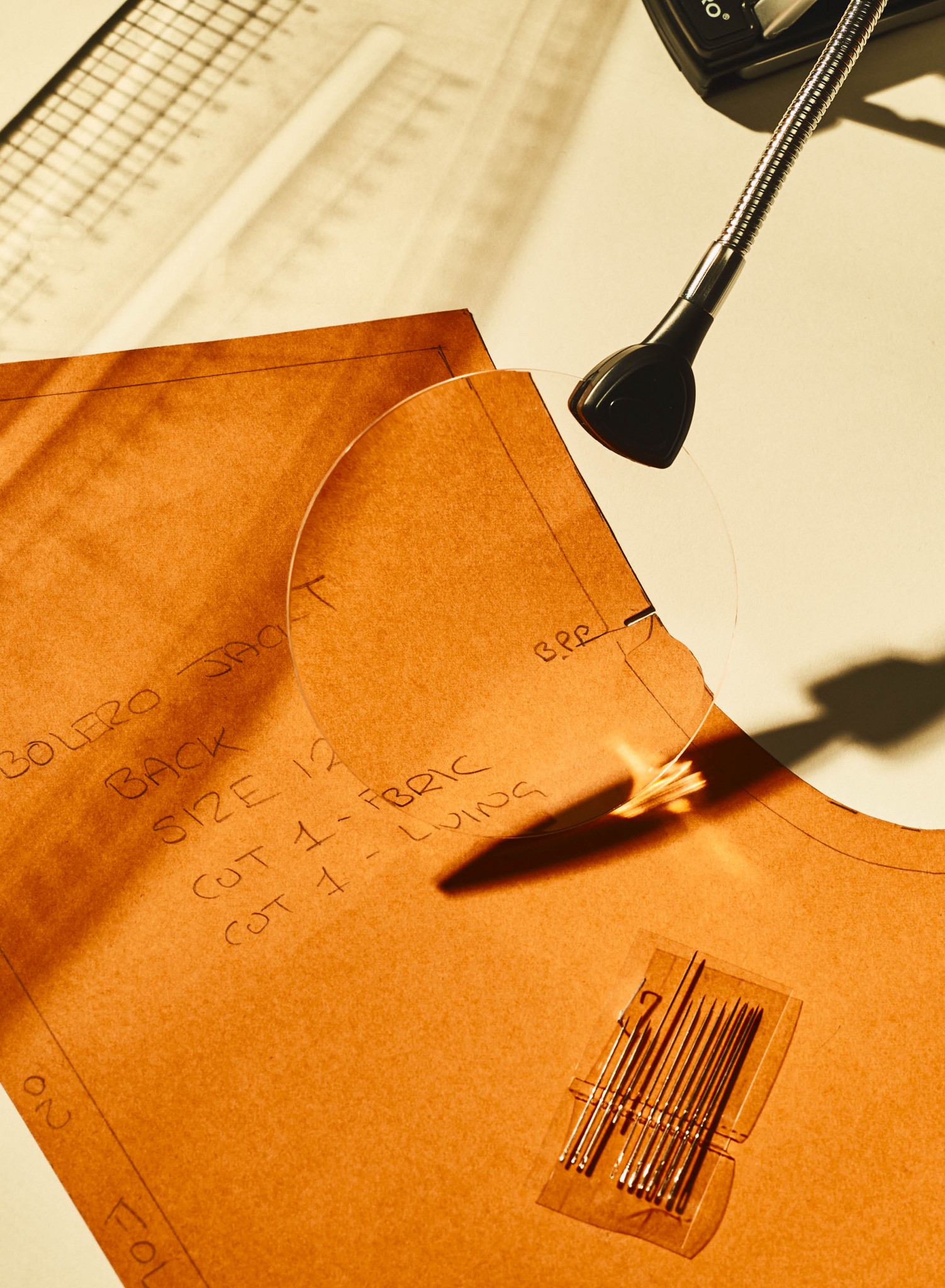

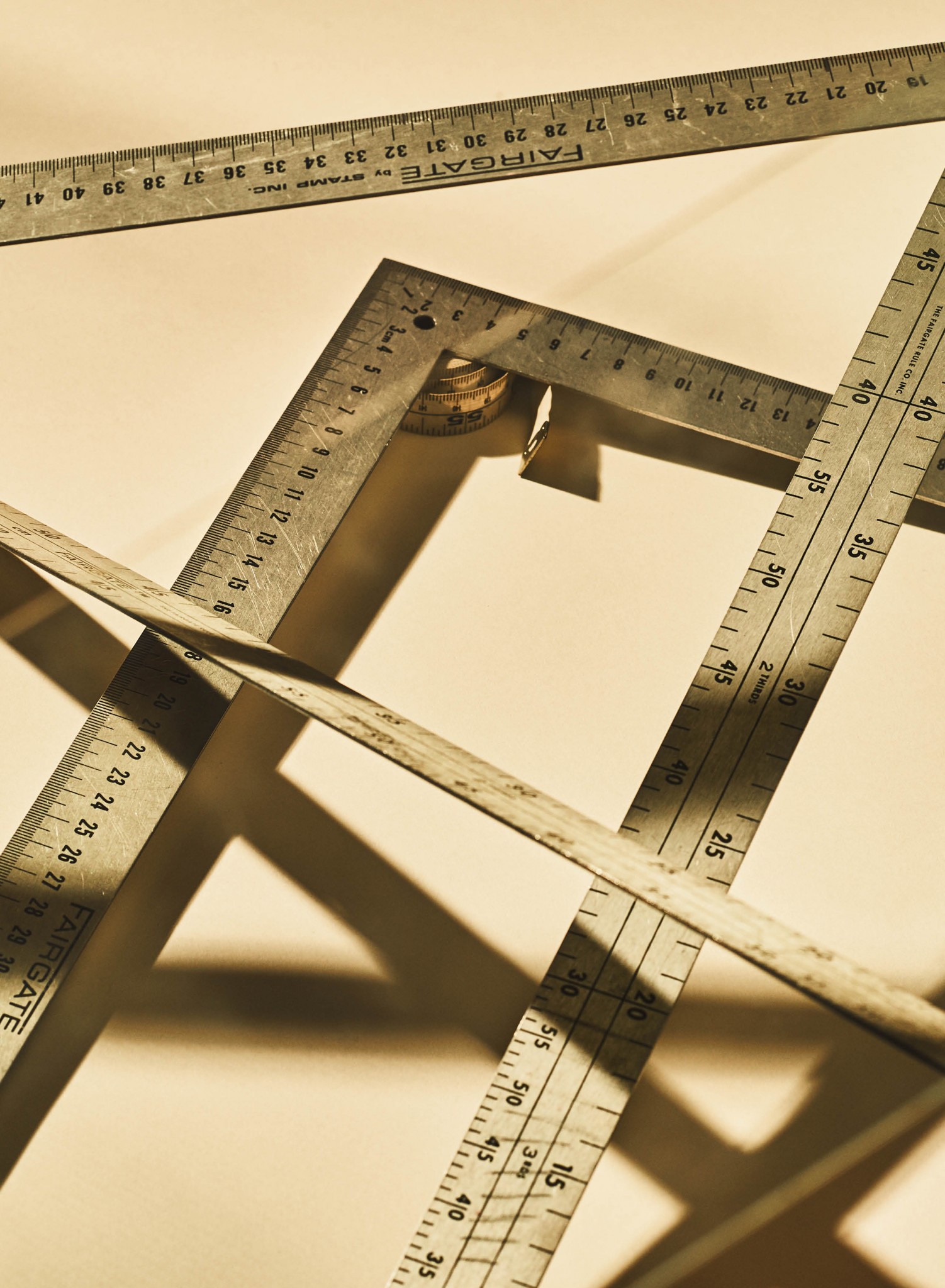

JF: Fashion design and pattern cutting courses are hugely popular in the UK and we are a globally recognised force in this part of the sector, but what we need are garment production skills, which is what our course at the Textile Training Centre offers. We teach excellent cut, manufacture and trim (CMT) skills to our trainees. This includes learning how to approach different seam types and lengths, zip insertions, pockets attachments, fabric handling through machines, lay-planning and bulk cutting.

JS: At the end of our eight-week course students receive a diploma, which helps them to find roles within the manufacturing sector. We work closely with many of the Scottish mills as well as placing them in London fashion sample rooms, which both helps employers to find new trainees, and helps our graduates in gaining employment.

What’s the government doing to help?

JF: While there aren’t currently any fashion-and-textile-specific initiatives, there are manufacturing and engineering initiatives that we participate in. So for instance, I’m attending meetings about the engineering sector around textiles and the need for both skilled operatives and new technology to support new starts in the industry, whether it’s equipment or machinery or the engineering of a garment scanner. In the future, I am also hoping we can work on something more specific to textiles and fashion to reflect the nuances of the sector; for instance, longer-term training in tailoring, or artisan hand embroidery skills.

PG: For a long time, the government has focused on the ‘sexy’ end of manufacturing – aerospace, pharmaceuticals and tech. Garment and textile manufacturing is technical! The UK produces incredible heritage fabrics but we also create woven carbons that feature highly in composite materials. Those applications encompass sports, the automobile industry and interior design. Textile applications range from the traditional to the super tech.

What are the benefits of reshoring production?

PG: It’s simple – increasing volume means higher efficiency, more investment in machinery and therefore rising employment. This lowers costs, so increases volume again, creating more employment, then, once again, triggering even more investment. It’s a very positive cycle that creates meaningful employment in towns that desperately need it.

JS: There’s also a reduction of carbon footprint, more efficient communication, and tighter lead times as a result of centrality to the market.

What challenges do you foresee?

JS: One of the challenges is an ageing workforce, followed by the perception of the sector. Because of the lack of investment in UK textile manufacturing in recent years, many retailers went off shore, so production capacity has dwindled, and as a result, so has employment, leaving us with a shortfall of skilled labour. In addition, the younger generation’s perception of the industry is not one of a cool and hip place to work, or even for that matter a career. It’s paramount to change this mentality and persuade the young that this can be a career for life, and that it’s fun – and very satisfying – to make things.

PG: I got involved with BBC’s The Great British Sewing Bee because I thought it would encourage people to start sewing again, which would be fantastic for our industry and for us as human beings who ought to be wearing clothes that last for a long time and know how to fix them. The show has been enormously successful and has made people think about their clothes in a different way. People started to look inside at the seams and think ‘oh that looks cheap, that’s not going to last’.

So changing perception is important?

JS: I think we all agree that it’s paramount. If we’re to grow UK textile manufacturing, we need more skilled labour, and this starts from the ground up. We have to change younger people’s perception that the industry is outdated – that in fact, there is a future and prospects once again.

JF: We also need to address the gender balance. To a lot of people, sewing is just home dressmaking – something maybe your granny did, but certainly not anything that a boy should engage in. With sewing, you’re working a piece of machinery, but young men don’t tend to really recognise tailoring as such, on the spectrum of practical skills.

PG: Savile Row tailoring was traditionally male-dominated – the women did the finishing, partly because the coal-heated irons used for the rest of the making weighed a tonne!

JF: I feel that we’ve lost our connection to that tradition. A lot of the boys we teach just presume it’s an Italian trade, they have no idea of our own heritage. They love the measuring and accuracy of working with the grading rule, and how you can use it you get a different effect. As a result, we’ve redesigned some of the products we create on our course to be gender neutral. We’re constantly adapting.

So how do you see the industry in the future – can tech and tradition work together even more successfully?

JS: Yes, absolutely. We mustn’t see technology and machines as a threat, they simply reduce the need for unskilled labour.

PG: Exactly! There is nothing particularly skilled about pressing the corners of a pocket, and a machine can do that in a second. The reason clothing and textiles first moved to Hong Kong, followed by mainland China, Bangladesh and Cambodia, is cheap labour. It’s getting very cheap and very dirty – people are starting to really worry about it. If technology means we’re no longer as reliant on this, then all of a sudden we give ourselves the opportunity to compete with those countries: we can do it well, we can do it locally, with sustainable fabrics, and we can create prosperity and community cohesion. It’s not just about Saville Row and fine hand sewing and £5,000 suits, I believe there’s a future for a broader spectrum garment manufacturing, which again provides a very solid and rewarding career for a lot of people.

JF: And that’s why we’ve got the chairmen that we’ve got. At the start of the project we focused solely on the heritage market, as we have a rich seam of traditional textile employers in Scotland, but Patrick and John bring a different viewpoint; they have a foot in industry, and can identify the kinds of projects and businesses, that can handle larger scale production, responsibly and sustainably. Those are the two guiding principles that inform all our work at the Foundation.